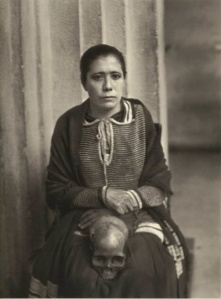

Dia de Los Muertos is a period of days when the souls of the dead return to visit the living, evoking the feelings and preparations surrounding a family reunion.

There has always been the understanding among families that the things we have in our lives are inherited from our ancestors: our homes, our furniture and household items, often the family business, our skills – our lives and our physical selves in a sense, are inherited from our ancestors, so we want very much to thank them and offer them the best.

When this feeling of good will is absent, any Mexican will tell you that we love resorting to scare tactics. Mexican children are brought up on a steady diet of rice, beans and fear.

Countless versions of this story are told, but they generally go like this:

Once upon a time, there was a man who did not believe in the dead and made no preparations for his dead parents. He went off with his friends as usual, and set out for home when the ceremonies were ending. He noticed that there were many people following him, but they were all were the dead returning to the other world.

Among them were his mother and father who were returning empty-handed, with no offering, whereas all the other dead were laden down with their gifts. His own dead carried only a piece of broken pottery as an incense burner, so that they burned their hands. They were crying and very sad.

Then the man no longer doubted, that the dead returned; he rushed home to set out his offering, and called for food to be brought. But, shortly after he started to feel sick and fell ill. A little while later he suddenly died. The food which he had ordered for the offering to his dead parents, became the the food at his own funeral.*

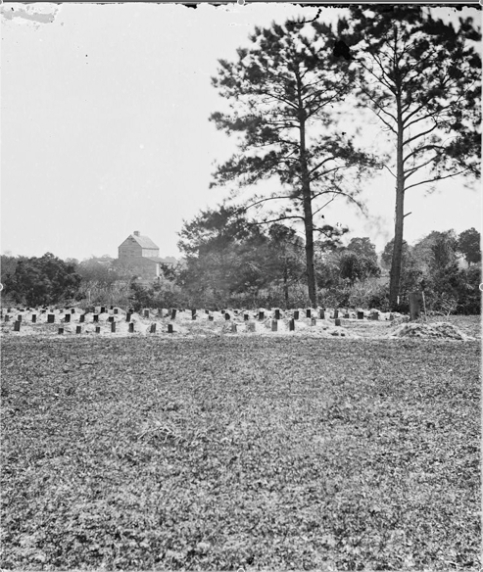

The key elements of the celebration include cemetery vigils, the erection of home altars, the preparation of special sweets, the presentation of flowers, candles and food to the dead and the performance of ritualized begging.

Symbols and Icons

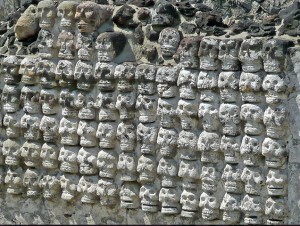

The ritualized begging is tied to one of Mexico’s most iconic objects, the sugar skull.

By the 1800s the wealthy were especially under pressure to give money, clothing and food to the poor when a family member died. It is in this context that the term, “a skull” – una calavera, was first used to signify funerary charity. The poor would go around the graveyards and approach funeral processions begging for “una calavera.” With regard to the calavera as donation, it is the poor who receive the contribution as the little skulls act as symbolic surrogates of the souls in purgatory.

A form of this tradition is still widely enacted each November, when families give gifts of calaveras in the form of sugar skulls to all the children they know, as well as assorted dependents and close friends. Children still go through the act of ritual begging when visiting friends and relatives on November 1st, by asking for their calavera, or as it becoming more the case their “Halloween.”

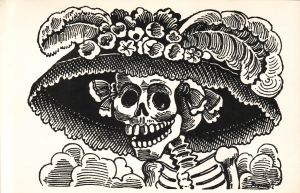

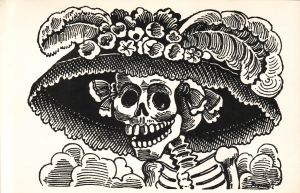

The other image most associated with Dia de Los Muertos emerged during the years following the end of the wars and just prior to the beginning of the Revolutionary period in 1910. Here, the image that would arguably define Mexico’s identity emerged, La Catrina Calavera.

José Guadalupe Posada was a Mexican artist who was known for his political art which frequently satirized the upper class.

His iconic etchings of skeletons dressed in upper class finery were intended as a satirical portrait of those Mexican natives who, Posada and many others felt were aspiring to adopt and value European traditions, values, and beauty standards in the pre-revolutionary era. This attitude of casting aside one’s culture, after centuries of incredible efforts to preserve it, was disheartening and infuriating to many.

Altars and Offrendas

The altars are made and decorated to display the offrendas – the offerings or gifts to the dead. These can be as simple as a table, decorated with a few key items, to incredibly elaborate and massive multi-tiered altars constructed by special builders.

Common gifts may be clothing, food, toys, personal objects and photographs. The dead should be provided with a basket or a special cloth to carry back all the gifts they have received. Anything the person enjoyed while living, we give to them in death.

Flowers are an important component, especially these yellow-orange marigolds, which we call cempasuchil or “flowers of the dead,” as the dead are especially attracted by both the color and scent. Not only are the flowers placed on altars and graves in abundance, but paths of the flowers can sometimes be seen leading to a cemetery or into a house to help the dead find their way.

Along these lines, copal incense and candles (long tall candles for adults, smaller versions for children) are very important. These are lit in homes and cemeteries to help ensure that the souls will not only find their way to their offerings at home, but back to the cemetery. During the days of the dead, the air is full with this beautiful, unforgettable light and warmth combined with the beautiful scent of the incense, flowers, and my favorite, food.

Food

There was a friar in the 1600s whose favorite pastime seemed to be spying on the surrounding indigenous people. He kept detailed records of everything he witnessed. One night, he followed some Indians into a huaca, where they interred their dead, and the friar confronted them, telling them how foolish they were to offer all this food to the dead, and asked them why they did it. One man answered:

“I know Father, that the dead do not eat the meat, nor the bones, instead they place themselves above the food and suck out all its virtues and the substance that they need and leave behind what they don’t need. And if this is not so, why do you allow the Spaniards to place bread, wine and goats on graves in the churches?” **

On November 1st when we receive the children, everything is made just for them and is done in miniature. Small versions or portions are served on little plates. Any food made, like tamales, are done without containing anything spicy. If a child died before it was weaned or was too little to drink from a cup you will sometimes see milk in a bottle on the altar.

A lot of candies are put out, many of them in the shape of skulls, skeletons or coffins.

Pan de muerto – bread of the dead, is everywhere. Traditionally, it is made in the shape of a little grave mound with bones or made to look like a corpse, (pictured below are some I made last year). You can find pan de muerto everywhere, both inside and outside the cemeteries, they are in every panderia and even at Starbucks.

After the souls depart, the food is enjoyed by friends, family and neighbors – it is a time for visiting people or for hosting them.

Root vegetables, carrots and jicama are eaten a lot around this time as it is believed that these things which grew under the ground were nourished by the corpses and this is another way we can be closer to the dead. Vendors selling root vegetables can be seen in some places outside the cemeteries and markets.

The Reunion

On the afternoon of October 31st it is time to receive the angelitos, the spirits of the children who have died. When the spirits of the children arrive, we imagine it as though they are coming out of school, happy and excited, all gathered to meet their loved ones.

The candles and incense is lit on the altars and people open the doors or go outside to receive them. Everyone sits near the altar and keeps them company.

The following day on November 1st, it is time for the adults to come and the same rituals are repeated. This is now a time for many to go to the cemetery to visit loved ones there.

Just outside the cemeteries, there are huge markets selling various flower arrangements, foods, toys and many things. The cemeteries are incredibly crowded and lively. Families carrying buckets of water up tall ladders to wash a grave, food vendors selling ice cream, children playing tag among the headstones or playing with toys right on top of a tomb.

Family pets are brought to visit, there are strolling musicians to serenade the dead, families having picnics and laughing – the love and joy shared with the dead during these days is something I wish everyone could experience.

Each town or region of Mexico has its own way of celebrating as a community as well.

In Iguala, the centerpiece of an altar is a rented coffin against a scenic arrangement and living tableaus featuring relatives of the deceased.

In Guanajuato, the streets are decorated with incredible flower pictures. Small bands in costume, often with traditional calavera make up, lead groups of people through the city singing songs of Mexico’s history and daily life. It is an interactive experience and the audience joins in on songs or playing various roles. In Zacatecas there is a huge carnival with rides and games with a two story Catrina presiding. At the entrance people picnic and watch movies surrounded by life size Catrinas.

Huaquechula is very unique in that families open their doors to welcome tourists into their homes – no one is turned away. The altars are a bit on the gaudy side. Everything is draped with white satin and all the altars have several statues of crying children on them.

In many cities there are processions around the center of town. People dress up in traditional costume – the majority of people are in calavera make up, but I have seen an alarming number of clowns in recent years.

In Chinahuapan, there’s the Festival of Light and Life. Here, visitors are led by torchlight on a procession through the nine levels of Aztec Hell.

The central days that most families observe are November 1st and 2nd – however, you can find some that observe this period from October 18th – November 30th. There are certain days when specific things are done, for example on La Vigilia everyone works hard putting the finishing touches on the altars. Or, October 18th in some places it is a day dedicated to the memory of those who have died tragically, particularly by drowning or assassination.

As time goes on these practices diminish and of course, not everyone in Mexico takes part in Dia de Los Muertos. Like in the US, by November 3rd you will see many shops throughout Mexico are already decorated for Christmas. There is also the matter of the American Halloween and its ever increasing influence on Mexico’s tradition, which has also served as a catalyst to revive and preserve these long held, sacred traditions.

_________________________

*Adapted from a story that appeared in The Skeleton at the Feast, Elizabeth Charmichael and Chloe Sayer

**English translation quoted from Death and the Idea of Mexico, Claudio Lomnitz